3 Very Common Survey Issues

October 16, 2018

The proliferation of survey tools and the advent of multiple digital touchpoints has made taking the market’s pulse easier than ever. The cost of administering a survey has fallen dramatically over the last few decades, and consumers are still open to sharing their thoughts. Slicing and dicing is lots of fun and requires little or no help from IT to create fresh reports. However, there are a few extremely common mistakes that many marketers make when it comes to survey design. And these mistakes lead directly to garbage data. So, let’s take out the trash!

Before we get into three very common issues, let’s level set. These mistakes are extremely common. They may not even appear to be mistakes to a casual observer. Folks with PhD’s who specialize in this area would be happy to share the science behind these insights through long-winded reviews of methodologies with equations that have a dozen Greek symbols described in excruciating detail through hours of boring lectures … or … you could just spend a few moments here. The latter is way quicker. Totally your call. Bonus: Copy this information into a PowerPoint to share with your colleagues and let them know how smart you are!

#1 — Less is More

Probably the single most common mistake when it comes to survey design is simply length. It’s one of those instances where less is more. Long surveys negatively impact completion rates, require more funds to secure completes and the results won’t actually reflect the market sentiment. For whatever reason, folks who have more than 30 minutes to take a survey are a bit odd . Their input won’t be representative of your target group, so it’s likely to be much less helpful. Short surveys also work better on mobile devices.

. Their input won’t be representative of your target group, so it’s likely to be much less helpful. Short surveys also work better on mobile devices.

Generally speaking, your ideal survey length should be 2 – 4 minutes. If it seems like a chore, it’s too long. One real danger of long surveys is that after a while people become much less careful with their answers. There is an increased likelihood of straight lining, which is very difficult to detect en masse and will certainly reduce the quality of the research. There are ways to identify straight lining, but it’s better to avoid it in the first place.

#2 — One at a Time

Often at odds with short surveys, is the seemingly unquenchable thirst for information. Often, this results in trying to generate several insights about more than one topic in a single question. This is a problem. Each survey question should be focused on uncovering a single truth. If you end up asking more than one question at a time, respondents will interpret the ask in multiple ways leaving you with worthless data.

Questions need to be carefully worded so that they get at a single, clear idea. Double barreled questions, also known as double-direct questions, are those that touch upon more than one issue, yet allow for only one answer.

There are a few common ways to determine if you’re double-barreling a question. Using the word “and” is a dead giveaway. For example, “How easy was it to set up your product, and how long did it take you?” Questions with multiple clauses or prepositional phrases are much more likely to be double barreled. Never write a question that follows the “If X, then what do you think about Y?” format. And avoid “Agree-Disagree” questions because they are rarely focused on a single, unencumbered insight.

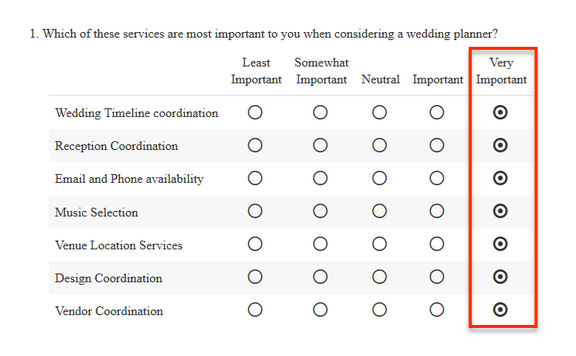

#3 — Scandalous Scales

Scales are often awful. There are simple best practices to getting them right. The two things to remember are that they should be Likert scales and that you should never use an 11 point scale.

Scales always need to be fully labeled with words. If you’ve got a dot, it needs a word. Interestingly, scales that use words provide more accurate results that those that use numbers. Scales numbered zero through ten are problematic because people see very little difference between responding with a six, seven or eight. Therefore your results will show some noise that shouldn’t actually be there.

Best practice is to use a five point Likert scale for unipolar constructs and a seven point scale for bipolar constructs. A unipolar scale starts from zero, has no natural midpoint and goes to an extreme. For example:

Do you trust this rickety bridge?

Do you trust this rickety bridge?

- I do not trust it at all.

- I trust it a little.

- I moderately trust it.

- I greatly trust it.

- I completely trust it.

A bipolar construct goes from one extreme (“extremely unhappy”) to another (“extremely happy”) and has a natural midpoint (“meh”)

How would you rate your experience with Blockbuster Video today?

How would you rate your experience with Blockbuster Video today?

- Extremely dissatisfied

- Moderately dissatisfied

- Somewhat dissatisfied

- Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied

- Somewhat satisfied

- Moderately satisfied

- Extremely satisfied

Closing Thoughts

Research is fantastic. We believe it’s fundamental to almost anything a business does, whether that research is internally or externally focused. Surveys can be a great tool, however survey design isn’t as simple as it looks. If you find yourself looking for an expert opinion, we’d love to share some guidance on survey design and corporate research methodologies or just to help you sift through the results. In any case, good luck!